.jpg)

Eastern Congo has earned the dubious title of being the rape capital of the world. It is estimated that 48 women are raped every hour – over 1,000 every day – in a conflict lasting over two decades.

By Joyce J Wangui

Twice in the past three years, campaigns to honour one man fighting to stem the tide have not succeeded in convincing the Nobel Peace Prize to award him, but a new documentary film makes a powerful case for his recognition.

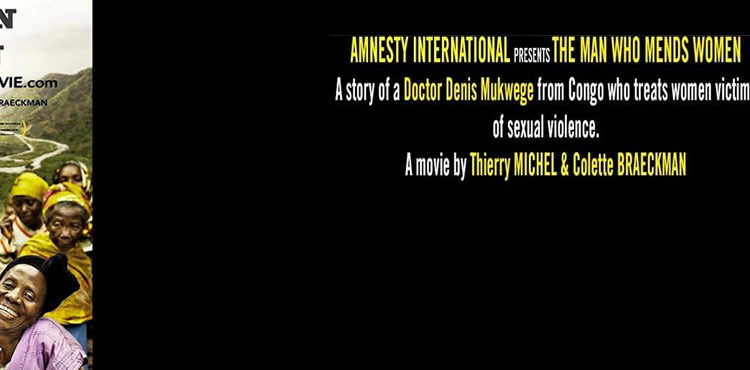

The Man who Mends Women: The Wrath of Hippocrates documents the struggles of Dr Denis Mukwege, a world-renowned gynaecological surgeon who treats survivors of sexual violence by repairing their damaged genitals.

Dr Mukwege vowed not stand idly by and watch a battle unfold on the bodies of women by founding Panzi Hospital in Bukavu. He has medically assisted over 40,000 sexually abused women in 16 years of professional work.

With tenderness and power, the 1h 52 -minute film directed by Thierry Michel & Colette Braeckman captures the magnitude of sexual violence in the Kivu province of the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, a place ravaged by decades of war, and exposes how this conflict threatens the wellbeing and future of Congolese women. It gives human faces and voices to fear, suffering, shame, trauma, and stigma associated with rape but also amplifies the resilience of these scarred women in trying to put their lives together. The film examines the various effects of rape on women – from the physical, psychological, emotional and even to the financial. It is a deliberate attempt to confront why women’s rights and reproductive and sexual rights have been trampled on and relegated by successive regimes.

Last year, Dr Mukwege recently received the prestigious Sacharov Prize for Freedom of Thought in recognition of his struggle against sexual violence. The film captures Mukwege’s outstanding mission of not only repairing lives but also defending human rights and raising global awareness towards sexual violence in the DRC.

For the past 15 years, Dr Mukwege has been battling to reverse the systematic and routine use of women’s bodies as battlegrounds, even at the risk of death. Three years ago, armed men entered his home and started shooting. Dr Mukwege and his family survived the attack, but his guard was shot dead. Today he works under heavy security provided by the United Nations. “If he disappeared, his death would be the death to all of us,” says a woman rape survivor in the film, who Mukwege operated.

Dr Mukwege does not only surgically repair his patients, he gives them a new lease of life-he restores their dignity. As the doctor desperately tries to search for answers, he implores men to look within themselves and put an end to sexual violence.

He fearlessly criticizes politicians and warlords for failing to address what has become his country’s greatest fault lines — war and rape. He advocates that perpetrators of sexual violence be brought to justice, including the Congolese government and militia groups laying siege on eastern DRC.

The film ends with a brave, poignant look into the heart of a country at the crossroads of changing the reputation of Eastern DR Congo as the rape capital of the world.

The film was shown in Nairobi on November 25, 2015, to public acclaim.