The Office of the Prosecutor wants the judge in the trial of Kenyan lawyer Paul Gicheru at the International Criminal Court to dismiss his application seeking to have 614 items excluded from the evidence list.

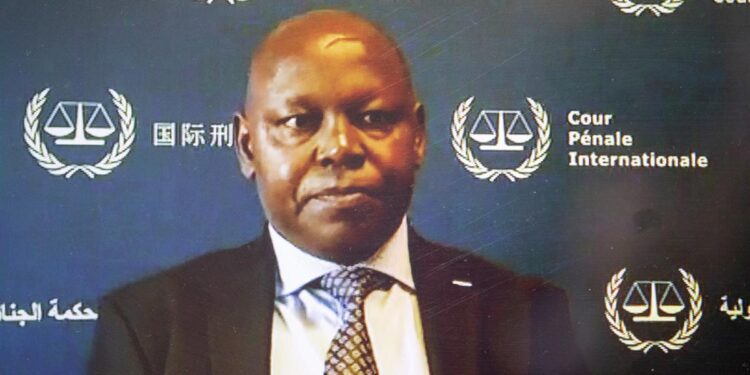

ICC Deputy Prosecutor James Stewart said 362 of the impugned items do not pertain to recordings made in the course of investigations under Article 70 on Offences against the Administration of Justice, under which Gicheru is charged.

He explained that the items, which he referred to as “irrelevant”, were obtained through a lawful process initiated through the prosecution’s request for assistance. He added that only 15 of the “irrelevant” items are listed as material that the Prosecution seeks to rely upon in evidence.

He also argued that the defence has not proved its allegation that the remaining 252 items were collected in violation of Part 9 of the Statute, which dwells on International Cooperation and Judicial Assistance.

“The prosecution consulted with the relevant authorities to the extent possible in the circumstances,” he said.

Stewart was replying to a request confidentially filed by Gicheru’s counsel, Michael G. Karnavas, dated December 17, 2021, asking Trial Chamber III’s Judge Miatta Maria Samba to exclude 614 items from the OTP’s list of evidence, claiming that admitting them would be “antithetical to and would seriously damage the integrity of the proceedings”.

The items in question consist of 30 audio recordings, 129 transcripts, 449 translations, and six summaries.

Outlining the factual context, the OTP said Kenya, as a state party to the Rome Statute, made it difficult to investigate the two cases from which the Gicheru matter sprung by refusing to cooperate with the prosecution, a fact that Trial Chamber V(A), which heard the case against Deputy President William Ruto and radio presenter Joshua Sang, described as “the withering hostility directed against these proceedings by important voices that generate pressure within Kenya at the community or national levels or both. Prominent among those were voices from the executive and legislative branches of the government.”

Stewart termed as “unrealistic and unconvincing” the defence’s claim that Kenya was fully cooperative with the prosecution in its investigation.

Defending the prosecution’s actions in obtaining some of the recordings the defence is objecting to, the Deputy Prosecutor explained that the telephone conversations were recorded as part of the investigation of witnesses’ complaints about attempts to corruptly influence them by people he described as “various members and associates of the common plan/purpose group” intent on carrying out the scheme. He said the prosecution decided to record the conversations in a bid to corroborate the reports.

He explained that the recordings did not take place on Kenyan territory, and were therefore not subject to Kenyan law, and that they were all made voluntarily by the witnesses in question. He said his office was under no obligation to warn the other parties that they were being recorded because they should have expected this to be a possibility as they were speaking to prosecution witnesses.

“The investigation of the scheme to corruptly influence witnesses was accordingly urgently needed, not only for the purposes of a possible future prosecution but more importantly to protect the integrity of the trial by attempting to avert the mass exodus of prosecution witnesses,” Stewart stated.

He agreed with the defence’s description of the investigation measures as “proactive” only in the sense that the prosecution sought to probe attempts to corruptly influence witnesses as they occurred and “covert” because the interlocutors were not advised that the witnesses were recording the conversations.

Gicheru, through his counsel, argued that the prosecution failed to observe the procedure of gathering evidence from member states.

Stewart further argued that the recordings were collected in the six months leading up to the commencement of the Ruto and Sang trial in September 2013, and at the height of the witness interference campaign.

He said the investigations depended on secrecy, therefore justifying sending investigators without informing state authorities. He explained that this was done in good faith and was essential for the investigative measures to be carried out without the presence of the territorial authorities, in order to preserve their effectiveness.

The prosecution said the lack of notification to the authorities was a harmless omission that does not materially alter the nature of its obligations under the Statute.

In any case, he said, the involvement of local authorities was not required as no interception technology or similar equipment used to intercept phone calls in the process of transmission, nor were similar compulsory measures used.

He added that this was also to protect the security of witnesses and the integrity of the trial in the Ruto and Sang case.

The prosecution said Gicheru’s internationally recognised human right of privacy was not violated as the recordings relate to the voluntary recording of conversations with other persons.

He described the evidence contained in the recordings as “precisely the same evidence about which the witnesses in question would undoubtedly be permitted to testify – merely preserved in a more durable and reliable format”, and that its admission would not harm the integrity of the proceedings.