Kenya’s rocky relationship with Somalia appeared headed for even more troubled waters as Nairobi withdrew its recognition of the compulsory jurisdiction of the United Nations’ International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the eve of a ruling on a maritime dispute between the two neighbours.

Kenya’s action signalled its intention to reject The Hague-based court’s decision, expected on October 12.

“The delivery of the judgment will be the culmination of a flawed judicial process that Kenya has had reservations with, and withdrawn from, on account not just of its obvious and inherent bias but also of its unsuitability to resolve the dispute at hand,” a press statement read by Foreign Affairs Principal Secretary Macharia Kamau on Friday, October 8, 2021 stated.

“Kenya… also joined many other members of the United Nations in withdrawing its recognition of the court’s compulsory jurisdiction,” he added.

Kenya’s tone was in sharp contrast to that of Somalia, whose Deputy Prime Minister, Mahdi Mohammed Gulaid, had earlier tweeted: “I am pleased to announce that the ICJ will render judgment of the case between Somalia v. Kenya on Tuesday 12 October, 2021 at the Peace Palace.”

Earlier this year, Kenya informed the court that it would not participate in the proceedings after the court declined to allow further adjournments that Kenya had requested ostensibly to prepare its case in the dispute that Somalia filed before the ICJ in 2014.

“This decision is on account of procedural unfairness at the court. It is a decision that was made after deep reflection and extensive consultation on how best to protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Kenya,” the statement dated March 18 said.

Among its grievances that led to its withdrawal from the proceedings, Kenya listed betrayal by Somalia and external interference by influential third parties “… intent on using instability in Somalia to advance predatory commercial interests with little regard to peace and security in the region”.

It challenged ICJ’s jurisdiction to hear the case and also took issue with the composition of the bench, which includes Somali national Abdulqawi Yusuf.

However, the ICJ on September 24 announced the date of its judgement.

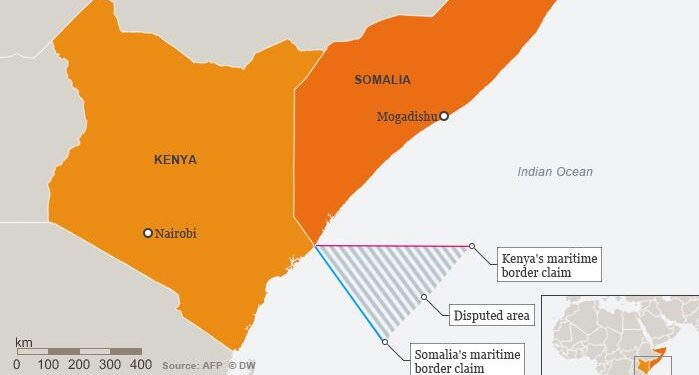

The two countries have for years been feuding over a stretch of the Indian Ocean, a triangle of water covering an area of more than 100,000 square kilometres (40,000 square miles), and believed to hold deposits of oil and gas. Kenyan fishermen rely on the area’s waters for their livelihood. Kenya insists it has had sovereignty over the contested zone since 1979.

The principle of compulsory jurisdiction of ICJ springs from the Statute of the International Criminal Court, which states, in Article 36(2) that “The states parties to the present statute may at any time declare that they recognise as compulsory ipso facto and without special agreement, in relation to any other state accepting the same obligation, the jurisdiction of the court…”

A member state that has accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the court is bound to agree with its decisions, which are final and without appeal.

By withdrawing from the case and the jurisdiction of the court, and signalling that it will not be party to its judgment, Kenya seems to be angling for other methods of dispute resolution. It has always pushed to have the disagreement settled through negotiation.

The ruling is likely to have ramifications for the stability of the Horn and the East African regions, and will affect the Indian Ocean stretch of the maritime borders shared by Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and South Africa.

This is not the first time a member of the UN has withdrawn from the mandatory jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court or rejected its judgment.

In rejecting the ICJ, Kenya was emphatic about protecting its territorial integrity and sovereignty.

“As a sovereign nation, Kenya shall no longer be subjected to an international court or tribunal without its express consent,” Kamau said.

The ICJ acts as a third party in resolving disputes between and among conflicting states to avoid war or engagement of a diplomatic crisis, according to international law.

Somalia instituted proceedings against Kenya with regard to “a dispute concerning maritime delimitation in the Indian Ocean” on August 28, 2014 at the ICJ. The president of the court fixed July 13, 2015 and May 27, 2016 as the respective time limits for the two parties to file their petitions (referred to as memorials).

In its four-volume petition, Somalia claimed that its southern boundary should run southeast as an extension of the land border. Mogadishu further intimated that the borderline should be a “median line” (which is formed of points at the same distance from both coasts), as specified in Article 15 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Kenya presented her preliminary objections on October 7, 2015, challenging the court’s jurisdiction to handle the case, and its admissibility. Secondly, Kenya argued that there was a signed MoU between the two countries in 1979, which established an arrangement providing for different methods of settlement, and that it gave her jurisdiction over the disputed area.

Furthermore, Kenya contended that Somalia’s border should take a roughly 45-degree turn at the shoreline and run in a latitudinal line.

On February 2, 2017, the International Court of Justice ruled that it had jurisdiction to proceed with the maritime delimitation between Somalia and Kenya. The oral proceedings were postponed several times between 2019 and 2021, when Nairobi boycotted the hearings, accusing the ICJ of unfairness, particularly the court’s unwillingness to delay the proceedings because of the impact of Covid-19. Public hearings were concluded on March 18, 2021 at the Peace Palace in The Hague. The court began its deliberations on September 24, 2021 and announced the ruling date for October 12, 2021.

Kenya and Somalia have sometimes had difficult diplomatic relations. Somalia has accused its neighbour of meddling in the affairs of regions in its territory. On October 16, 2011, Kenya Defence Forces troops pursued members of Al Shabaab terrorist group into southern Somalia after they orchestrated a series of attacks and kidnappings of tourists along the border. The troops stayed on under the African Union Mission in Somalia (Amisom).

In May 2019, Somalia criticised Kenya for deporting two Somali legislators and a minister after authorities in Nairobi denied them entry at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. In March 2020, Somalia banned the importation of khat from Kenya, claiming it was to contain the spread of the coronavirus. However, it allowed imports from Ethiopia.

In December 2020, Somalia cut diplomatic ties with Kenya, accusing it of meddling in its internal affairs. The relations have since been restored.

Analysts reckon the ICJ ruling will have far-reaching ramifications, not only for the disputed mass of water, but across the whole spectrum of relations throughout the East Africa and Horn of Africa regions. The area attracts significant international attention due to security threats emanating from Somalia. Kenya is heavily involved in peace keeping activities in Somalia and this might be affected.

“Whichever way the ICJ rules, it will be a bombshell that will reverberate far and wide in the region where diplomatic relations are deteriorating,” said Hassan Hussein, a Horn of Africa security analyst.

ICJ rulings are binding, although the court has no enforcement powers.

For a map see:

www.dw.com/en/kenya-or-somalia-who-owns-the-sea-and-what-lies-beneath/a-195572