As the International Criminal Court celebrates 25 years of the Rome Statute this year, the Sudan situation will almost certainly feature on the court’s list of its own successes and failures as it looks back on its almost 21 years of existence.

For almost two decades, the ICC has been trying to pursue justice for the victims of the atrocities committed during the conflict in Darfur, Sudan. When the United Nations Security Council referred the situation to the ICC in March 2005, the court was just three months short of its third birthday. It set a fast pace, with the Prosecutor starting investigations in June 2005 and the judges issuing the first arrest warrants two years later.

Although the Sudan case has crossed the desks of all the three ICC prosecutors, not much has happened to bring the quest for justice for the victims any closer. So far, although the court has issued seven arrest warrants against six people, including the then President Omar al Bashir, only one of the suspects is on trial. Four others with outstanding arrest warrants – Ahmad Harun, Abdallah Banda, Abdel Raheem Muhammad Hussein, and Bashir – are still at large. They face several counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Bashir faces an additional count of genocide. This makes him the first person to be charged by the ICC for the crime of genocide. Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s repeated attempts to enforce the arrest warrants and gain government cooperation, including a visit to Khartoum in 2021, just before her departure from office, were largely unsuccessful.

However, the years of the efforts of Bensouda and her predecessor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, were rewarded with the surrender of Ali Muhammad Ali Abd-Al-Rahman, also known as Ali Kushayb, who came into the custody of the ICC in June, 2020. The charges against him were confirmed in July, 2021, soon after Karim Khan started his term as the third Prosecutor of the ICC. Abd-Al-Rahman’s trial, which opened in April, 2022, is counted as one of the encouraging developments in the cases resulting from the Sudan situation.

Getting some or all of the four men with outstanding arrest warrants in custody and on trial would be a great triumph for the ICC. This seems to be one of the priority tasks Khan set himself as he settled into his new office, and he seemed to be targeting the biggest prize of them all – Bashir.

He appeared to hope to break the deadlock and get the Sudan cases going, and therefore succeed where his predecessors have failed. He said only a new approach would yield results if cooperation from Sudan isn’t forthcoming.

“I think through the adoption of the new strategy, by new resources, by running investigations more diligently, we can ensure that steps towards justice continue to be taken,” Khan said.

The Darfur situation has been nothing but complicated. After the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Bashir in 2009, the “all-too-powerful” leader was re-elected in 2010. This further dampened the ICC’s efforts to bring the perpetrators of the Darfur conflict to trial. The situation was not helped by the refusal of states he visited, including South Africa and Jordan, to arrest the Sudanese president despite the fact that as states parties to the Rome Statute, they are obligated to.

But the situation changed in Sudan, perhaps giving Khan hope of success. For one, Bashir was overthrown in a popular uprising in 2019, and the Transitional Government made up of both civilians and army generals that was in place until October 2021 had expressed its willingness to cooperate with the ICC.

You Might Also Like: State’s refusal to cooperate poses danger to justice in Sudan, Khan warns

It also signalled a change in its position in regard to human rights and civil liberties. In August 2021, the Transitional Government, led by former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, ratified the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. It also complied with the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. It heralded the repeal of public order laws that had long been abused by targeting women for a range of morality offences.

While the uprising that ejected Bashir from the seat of power was a significant happening that appeared to have the potential to expedite the progress of the ICC investigations in Sudan, the accountability and reform objectives that sought to establish a transitional government with real, structural implications for different components of the country’s security apparatus or for specific individuals, were never fulfilled after the military leaders staged a coup in October 2021 to remove the civilians from transitional administration. This has had the effect of further prolonging the wait for justice for the Darfur victims as all the promised reforms were suspended. For one, it stalled the country’s ratification of the Rome Statute, leaving it in the hands of the military-led Sovereign Council. Additionally, the long-awaited arrest and transfer of Bashir and the other suspects to the ICC seem to have been taken off the table.

When Khan took office, he vowed to prioritise the pursuit of justice in Darfur. He appeared ready to change his strategy in order to get results by avoiding what he termed starting too many cases with little chance of success. He promised to pursue only the cases that were likely to lead to successful prosecutions – and it appears Darfur is one of them.

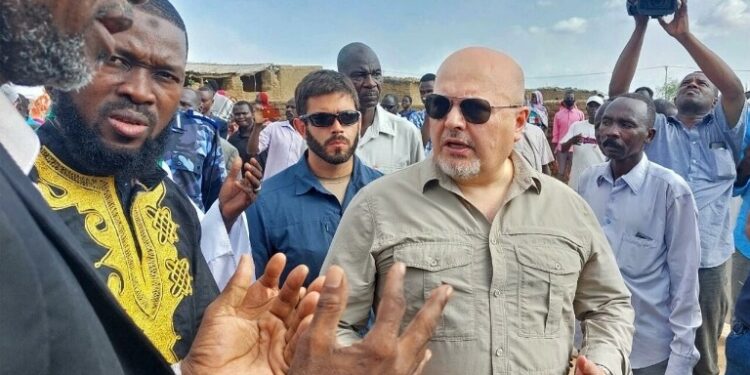

Therefore, it was with great optimism that he made two visits to Khartoum – in August 2021 and August 2022.

He met with government officials and victims’ groups to discuss the ICC’s mandate and the importance of accountability for the crimes committed in Darfur. The visits were a success, or so it seemed, producing a new memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Sudanese government in relation to the four outstanding ICC arrest warrants. The Sudanese government and the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor agreed to work closely with other stakeholders to implement the agreement.

While signing the agreement, Khan urged the Sudanese authorities to provide immediate and full access to any evidence to aid his investigations. He noted that the collaboration would finally help bring justice to the victims.

“After almost 17 years since the referral of this situation, the Government of Sudan and the ICC owe to the victims of atrocity crimes in Darfur justice without further delay,” he said.

The Prosecutor’s renewed expectations were apparent in his presentation of the 34th report on Sudan when he briefed the UNSC on January 17, 2022. H spoke about the measures he had taken to move the case along. These included allocating additional resources such as more investigators to the team, including people with Arabic language skills, and the appointment of pro bono Special Adviser Amal Clooney, a human rights lawyer.

He also told the Security Council that the Sudanese government had committed to working closely with his office and to support the signing the Rome Statute, and had agreed to facilitate the presence of a full-time ICC field office in Khartoum.

Despite the challenges, Khan remained optimistic about the possibility of cooperation. He praised the government’s willingness to cooperate with the ICC and expressed hope that justice could finally be served for the victims of the Darfur conflict.

In April 2022, the Prosecutor opened the Abd-Al-Rahman case. To Khan and the victims of the Darfur atrocities, this marked a milestone in the court’s efforts to try those responsible for the war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Sudan. During his second visit to Sudan in August 2022, Khan told the UNSC that the trial had a tremendous impact on the people of Darfur.

“I think its importance cannot be overestimated,” Khan commented. “This is a massive commendation to the persistence, the resilience, the courage, and belief of the Sudanese people. Words simply are insufficient to give them their due, that even in the very dark days of non-cooperation with Sudan, they believed that a day would come where justice would be delivered.”

However, his tone has change over the ensuing months as the promised Sudanese government cooperation has remained elusive.

While delivering the ICC’s 36th report on Darfur to the UNSC on January 25, 2023, Khan acknowledged that the MoU had not been honoured, and cooperation has not improved.

“My report attempts to fairly and accurately set out the unfortunate gap existing between the words and the action of the Government of Sudan,” he said.

The challenges the ICC staff has faced include difficulty accessing the country to conduct investigations as previous commitments of making available to them multiple entry visas have not been delivered.

“Even when ICC staff have entered Sudan, they must wait for internal travel permits, including to go to Darfur. The court also has not received assistance with accessing public locations such as the National Archives, nor formal approval to establish an office in Khartoum,” the Prosecutor said.

However, Sudan’s Ministry of Justices, the main channel of communication regarding the situation in Darfur, denied it had impeded any investigations.

“We have received a number of requests for assistance from the court in the past, and all of them were responded to. Sudanese authorities cooperated with the ICC to achieve justice,” it said in a statement in August 2022.

As the cases in the situation appear set for more years of inaction as Khan’s new approach appears to stall, the victims of the conflict continue to live in fear and insecurity. Many of the perpetrators remain at large and continue to threaten the peace and stability of the region. The reluctance of the Sudanese government to help apprehend these individuals will continue to impede progress in the case.

Khan might have to go back to the drawing to confront the challenges facing the ICC in its quest to get justice for the victims of the Darfur conflict.