By Henry Gekonde

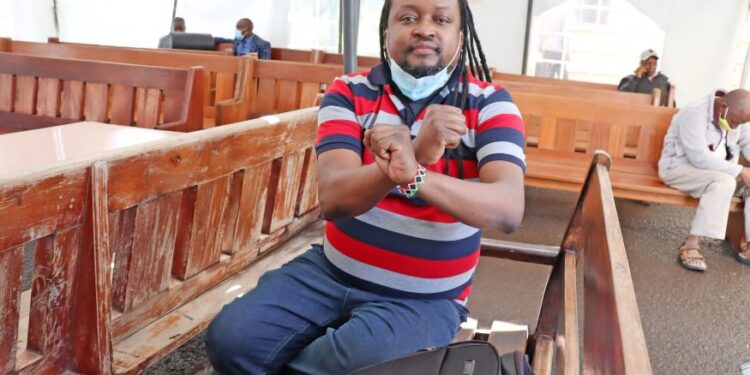

A Kenyan social media activist is out on bail as he fights cybercrime charges that could send him to prison for up to two years if he is convicted. The authorities have linked Edwin Mutemi Kiama to several social media accounts publishing content critical of government policies and programmes. He is charged under the controversial Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, which was adopted in 2018 in response to rising cases of cyberattacks targeting banks, institutions, and state agencies.

The alleged crime

Kiama is accused of publishing false information about President Uhuru Kenyatta, who is nearing the end of his second and last term in office. His arrest and subsequent charging in court was sparked by a decision made a few days earlier seven thousand miles away in Washington, DC.

On April 2, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced it had approved a new three-year, $2.34 billion loan for Kenya to aid efforts against Covid-19 (which has infected 147,000 people and killed about 2,400) and “reduce [its] debt vulnerabilities” (Kenya’s national debt stood at $65 billion as of November 2020).

The IMF decision enraged many Kenyans, scores of whom took to social media to vent their anger at what they see as an increasingly unmanageable national debt burden. One such critic is Kiama, who is accused of creating a notice depicting a photo of President Kenyatta with unflattering text, and posting it on Twitter. The artwork was widely shared on social media, with its message becoming fodder for the ongoing debate about Kenya’s indebtedness.

The image, styled in the fashion of legal notices often published by companies in local newspapers about disgraced former employees, said: “This is to notify the world at large that the person whose photograph and names appear above is not authorised to act or transact on behalf of the citizens of the Republic of Kenya and that the nation and our future generations shall not be held liable for any penalties of bad loans negotiated and/or borrowed by him.”

This is not Kiama’s first court case arising from his internet activities. In June 2020, police broke the front door of his home and arrested him on what was initially reported to be a charge related to copyright infringement and book piracy. He was presented in court, charged with computer crimes. That case is still pending.

Internet access and cybercrimes

As more Kenyans acquire smartphones and tablets, greater numbers of them are getting connected to the internet. Kenya has the third-highest rate of internet penetration in Africa (after Nigeria and Libya), according to market and consumer data provider Statista.

While greater access to the internet is a boon for Kenyans – such as enabling easier mobile financial transactions and digital loans, and allowing citizens to bypass the filters of traditional media in expressing their views about the government and its policies – it has its pitfalls. These include cyberattacks against organisations to steal information or money, and malicious or mischievous hacking motivated by the thrill of simply defacing the websites of companies and institutions.

In May 2017, Kenyan communications regulators reported that about 20 companies had been hit by the WannaCry ransomware attack that was said to have affected more than 200,000 computers in 150 countries. Several Kenyan banks have also been targeted by local hackers. One man, Alex Mutuku, in his early thirties and described as Kenya’s ‘best’ cybercriminal, is battling several court cases in which he has been accused of hacking into banking systems and stealing millions of shillings, and breaking into the computer systems of government agencies.

These are some of the cybercrimes that prompted the Kenyan government to adopt the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act in 2018. Section 22 (1) of the law says in part: “A person who intentionally publishes false, misleading or fictitious data or misinforms with intent that the data shall be considered or acted upon as authentic, with or without any financial gain, commits an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to a fine not exceeding five million shillings or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years, or to both.”

It also says that although the country’s constitution protects freedom of expression, that right is limited “in respect of the intentional publication of false, misleading, or fictitious data or misinformation”.

Cybercrime law and its critics

Opponents of the law, including civil liberties groups, lawyers, and academics, say it has opened the door for the government to invade the privacy of citizens and has had a chilling effect on the right to freedom of expression.

“State-sanctioned intimidation and harassment of activists who use online and offline tools and platforms to protest and express themselves, using creative and artistic tools, on social and political issues must become a knee-jerk reaction of the past. The state is attempting to water down the sanctity of the right to protest and the right to freedom of political expression, but their primacy in the Constitution cannot be shifted,” said Mugambi Kiai of ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa, which promotes freedom of expression and freedom of information.

Critics of the law also argue that these crimes were already covered under existing legislation and the penal code. They are concerned that the law lacks details about how it is supposed to be enforced and is, therefore, likely to be interpreted by overzealous security officials as allowing them to eavesdrop on conversations and collect data on citizens in nefarious efforts to silence legitimate political expression. The law also criminalises the publication of “false information” and “hate speech”, though it does not define what “hate speech” is.

When the law came into force in 2018, it was challenged in the high court by the Bloggers Association of Kenya, whose lawyers argued that portions of the legislation violated constitutional provisions related to media freedom and freedom of expression. A high court judge dismissed the bloggers’ case in February 2020.

What’s next in the case

The backlog of cases in Kenya’s courts is noteworthy and a matter of great concern for judiciary officials. Official statistics released in 2019 showed that by June 2018 about half of unresolved cases had dragged on for more than three years, with magistrate courts and the high court registering the highest numbers. The logjam likely remained or worsened through 2020 as the country shuttered its courts as part of movement and social-distancing restrictions meant to stem the spread of Covid-19.

Kiama has a court date in his new case in two weeks. If he is lucky, the most likely outcome he can expect at the hearing is getting another date for yet another hearing. Such delays are so common in the Kenyan court system that they have themselves become a distinct form of injustice. While Kiama awaits his next court date, the magistrate hearing the case has gagged him, ordering him not to share any messages or images on Kenya’s foreign debt or on President Kenyatta.

Mr Gekonde is a freelance writer, editor, and researcher with more than 20 years in newspaper and book publishing in the United States and Kenya, most recently with the Daily Nation.