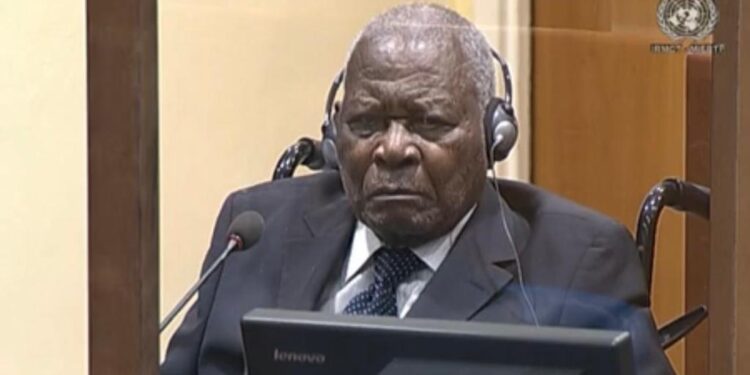

Alleged Rwandan genocide financier Félicien Kabuga is scheduled for another court-ordered status conference on September 25, 2025, as judges, lawyers, and diplomats grapple with what to do with the ailing 92-year-old, whose provisional release has stalled as no country will accept him.

According to the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT) notice dated August 11, 2025, judges Iain Bonomy (presiding), Mustapha El Baaj, and Margaret M. deGuzman, sitting at its branch in The Hague, will hear from both the prosecution and the defence submissions about Kabuga’s condition, his release options, and “…any issues normally addressed during a status conference…” Because of his health, he is expected to attend via video link from the UN Detention Unit in The Hague. A public recording of the hearing will be made available only after the proceedings have concluded.

The office of the prosecutor includes Serge Brammertz, Rashid S. Rashid, Rupert Elderkin. Kabuga’s counsel is Emmanuel Altit.

The status hearing is scheduled to take place a few months after the last one, held on May 1, 2025. Since the trial chamber indefinitely stayed the proceedings against Kabuga in September 2023, after affirming that he was not fit to stand trial and was unlikely to ever regain that fitness, other status conferences were held on December 13, 2023, March 26, 2024, July 24, 2024, and December 11, 2024.

Kabuga, one of the world’s most wanted fugitives, was arrested in France in May 2020 after more than two decades on the run. He was accused of bankrolling and supplying the Interahamwe militia, and helping to set up Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, which helped to fan the 1994 genocide in Rwanda by spewing hate propaganda. More than 800,000 people, mostly Tutsis, but also moderate Hutus, were killed.

Too sick to stand trial

Independent medical experts have found that he suffers from advanced dementia and other severe age-related health problems, leaving him unable to participate in his defence.

“The experts agree that Mr Kabuga remains unfit to plead or to stand trial, as well as medically unfit to travel,” the court said.

Two forensic psychiatrists offered differing views.

“Mr Kabuga’s cognitive decline was limited and he did not show the characteristics of dementia. He could participate meaningfully in a trial if provided with appropriate assistance,” Prof Henry Kennedy stated in his Medical Report to the IRMCT.

In contrast, Prof Gillian Mezey concluded that “Mr Kabuga had moderate to severe dementia that was progressive in nature.”

Earlier this year, Dr Gert Muurling, a court-appointed medical expert, confirmed Kabuga’s poor health and said he was not fit to travel. He added that air travel could be possible with strict precautions, but overall, it was not advisable.

ALSO READ: Elusive Sanna Manjang continues to rob Gambian victims of hope for justice

The court’s ruling didn’t end the case. Instead, proceedings were “indefinitely stayed”, meaning the case is technically still active, with regular updates and hearings to review his condition. Critics say this has created a legal limbo that achieves little when the medical prognosis shows no chance of improvement.

For many survivors of the genocide, the situation is heartbreaking. They waited for more than 25 years for Kabuga’s arrest, only to be told there would be no trial.

In August 2023, the genocide survivors’ group Ibuka, voiced concern about the UN tribunal’s decision to indefinitely pause the proceedings and warned that the suspension threatened to undermine the survivors’ trust in justice.

“The ruling to potentially release Kabuga is a deliberate insult to the deep wounds that genocide survivors suffer,” Naphtali Ahishakiye, Executive Secretary of Ibuka, told the AFP. “Aligning with a court that continuously shields genocide perpetrators at the expense of justice for survivors has lost its rationale.”

The Kabuga case highlights the challenges of international justice when arrests come long after crimes are committed. When Kabuga was first indicted in 1997, he was in his sixties and healthy enough to face trial. Two decades later, his physical and mental state have made prosecution near impossible.

Humanitarian release — with nowhere to go

Kabuga’s defence team has repeatedly pushed for his provisional release on humanitarian grounds, arguing that at his age and in his condition, keeping him in custody is pointless and inhumane. But there’s a catch: “No state which Mr Kabuga has identified as one where he wishes to go has agreed to accept him,” the court noted.

This reluctance reflects not just his notoriety, but also the diplomatic and political complications of hosting an elderly man accused of financing a genocide.

Kabuga’s predicament is not unique. Former Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević died in custody in 2006 before his trial concluded. Ratko Mladić’s proceedings have also been shaped by concerns over his age and health. Such cases present difficult questions: When does the humanitarian imperative override the pursuit of justice? And what responsibility does the international community bear when no nation is willing to accept even a medically supervised accused person?

Further to these questions is the fact that the Kabuga case is emblematic of broader criticisms of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and its successor, the IRMCT. Despite spending hundreds of millions of dollars over decades, the tribunal has been accused of delivering limited justice and failing to meet the expectations of survivors. It is seen by some as the final failure — a “white elephant” of justice that enriched lawyers and judges but left victims without genuine closure.

Justice for CAR victims as ICC sends two militia leaders to prison for brutal crimes

The IRMCT, which remains responsible for Kabuga’s detention and medical care, even as its mandate is to wrap up the ICTR, finds itself at a crossroads. The court must balance its judicial mandate with humanitarian considerations, while at the same time navigating the diplomatic realities of a world where no country wants responsibility for an aging, infirm accused genocide financier.

For some observers of international justice, Kabuga’s and other comparable cases make it imperative for the international community to confront this dilemma — either by creating mechanisms for such exceptional instances or by acknowledging that some chapters of international justice may remain unresolved, not due to lack of willingness, but the inescapable realities of human mortality and international politics.