Rape, one of the grossest violations of humanity, has been hard to try in local and international courts for lack of evidence.

By Joyce J Wangui

A hush usually falls on the room when Jacqueline Mutere, 49, begins to speak about her rape at the hands of her neighbour during the 2007/2008 post-election violence.

Standing at six feet, seven, she is dry-eyed, but her face is taut with emotion that says: “I know him.” Knowing her attacker has not helped her to get justice. She went to see a doctor two days after she was raped.

“While I knew it was important to see a doctor, and I tried to get to the hospital and the police station, the institutions did not have proper infrastructure to ensure that I received justice,” Mutere adds.

Mutere soon realised that she was pregnant and had no option, but carry the baby – her fourth – to term. The conflicting emotions of raising her drove her to found Grace Agenda, an organisation started to take care of children from rape but now also help survivors of sexual violence to deal with the aftermath of the violations.

The mother of four says she is concerned by the rising cases of rape and few convictions. Sexual violence has become part of the culture of crime in Kenya.

The latest State of the Judiciary and Administration of Justice report notes that sexual offences cases in the courts rose from 7,727 in 2012/13 to 13,828 in 2013/14. And that is just a tip of the iceberg. Statistics from a 2012 government survey show that one in three Kenyan girls is sexually violated before the age of 18 years. Every 30 minutes, a woman is raped in Kenya, but only one in 20 cases is ever reported.

Hundreds of women, girls and men sexually violated during the post-election period are still battling with trauma as they await the outcome of a case they filed at the High Court against the Kenya Government in 2013 for failing to protect civilians and subsequently investigate cases of sexual violence that occurred during the 2007/2008 chaos.

Although the Judiciary is seen as robust, corruption in the ranks of the criminal justice system and intimidation of survivors and witnesses continue to deny many survivors justice and reparations. Failure to prosecute perpetrators, even in situations where they are known, and where circumstantial evidence is available, is the greatest impediment to delivering justice for victims and communities affected by rape.

A senior counsel who deals with sexual offences at the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions says poor investigations hamper the search for justice because they make it hard to tie the survivor’s story with evidence linking the suspect to the crime. As a result, many sexual violence cases do not even enter the court system.

“The Penal Code and the Sexual Offences Act, as well as the entire legal system, is formidable but the medico-legal mechanisms for mitigating sexual violence are still docile,” said the prosecutor, who declined to be named because she is not authorised to speak on behalf of the DPP.

Loose legal ends

Every week, the prosecutor works with the police to gather evidence against suspected rapists, but she is hampered by their lack of expertise. “A case is won or lost at the investigation stage. If proper investigations are not carried out by the police, prosecutors cannot ‘manufacture’ evidence,” she adds in frustration.

The inadequacies of police investigators in sexual crimes frustrate the collection of crucial evidence to build a case that would result in a conviction. “If our police were trained, then these cases could not be presenting so many loopholes,” she said.

Low quality police work is not the only loose end, however. Government efforts to set up gender desks in many police stations to respond to sexual and gender-based crimes are not supported by sufficient trained, designated staff and equipment.

At the Kayole Police Station, in Nairobi, the gender desk is not staffed. Anyone reporting a sexual crime is attended by any available officer, trained or not. Officers, particularly in this low-income area, often prioritise other grave crimes such as murder, robbery with violence and assault and battery, but relegate sexual violence cases.

At the Pangani Police Station, Nairobi, which serves an area with a high incidence of sexual violence, officers are not trained in the collection, documentation and preservation of evidence.

No broken hymen

For many years, Kenya has only had one male police doctor based at the Nairobi Area Traffic headquarters. He would examine complainants in order to fill in the official form – the P3 – a survivor can use to seek justice. Overwhelmed by the many cases of rape he had to deal with, overstretched by work, and lacking the skills to collect samples, the doctor would only need to sign off with the three words: “No broken hymen”.

Police, however, are not the only first responders to sexual violence cases handicapped by lack of expertise. Specialised forensics training has previously targeted only a few senior doctors and the upper echelons in police service. Lower level staff, who are often the first people to receive and attend to survivors of rape, are not usually reached.

John Mungai, a forensic analyst at the Government Chemist based at the Kenyatta National Hospital, says one of the biggest challenges in prosecuting sexual violence is the lack of a DNA bank for sexual offenders.

“We rely entirely on a comparison process, that is, where there is a suspect, DNA samples are taken from him and compared to those from a crime scene; and if it is a sexual offence that leads to pregnancy, DNA samples are taken from the parties concerned,” he says.

Mungai says staff in the Government Chemist laboratories do not have adequate training to handle and analyse forensic material in rape cases.

Lost in translation

Justice Stephen Githinji, who was recently promoted to the High Court, has heard many sexual offences cases as a magistrate in Naivasha. He notes that most judicial officers are frustrated by the medical jargon used by doctors in the courtroom. “A case may be lost because the judicial officer does not understand the kind of evidence the doctor is tabling.” There are times when crucial details in the medical certificate are missing, for instance when clinicians fail to document the history of the victim, or investigators file cases without key evidence from a crime scene – such as a sketch, photographs as well as details of what was found at the crime scene.

Despite the enactment of the Sexual Offences Act in 2006, perpetrators continue to slip through the legal system unpunished.

The law requires the Registrar of the High Court to keep a register of convicted sexual offenders and a data bank, but it has not been established. Without such records, Judge Githinji explains, suspects are likely to be treated as first-time offenders.

Forensic training

For ages, rape has been used as a weapon in wars. Consequently, it is one of the atrocities that form many cases brought to the International Criminal Court at The Hague. However, rape, one of the grossest violations of humanity, has been hard to try in local and international courts for lack of evidence. To mitigate this, the Office of the Prosecutor at the International Criminal Court has agreed to work with Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). Through the training of first responders, it is hoped that many legal loopholes that allow perpetrators to go scot-free can be sealed. Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo are among the first beneficiaries of the partnership.

Karen Naimer, who leads PHR’s programme on Sexual Violence in Conflict Zones, says her goal is to train health professionals, law enforcement officers, lawyers, judges and community health workers to properly collect and document forensic evidence in sexual violence cases. Their ultimate goal is to ensure that survivors get justice.

DNA analyst Christine Matindi, who works at the Government Chemist in Kenya, was first trained by PHR in 2014 on exhibit collection, drying of samples from a rape victim. “The kind of training PHR offered me is not being offered by the government,” she says. Officers are often thrown into the deep end of work and encouraged to learn on the job.

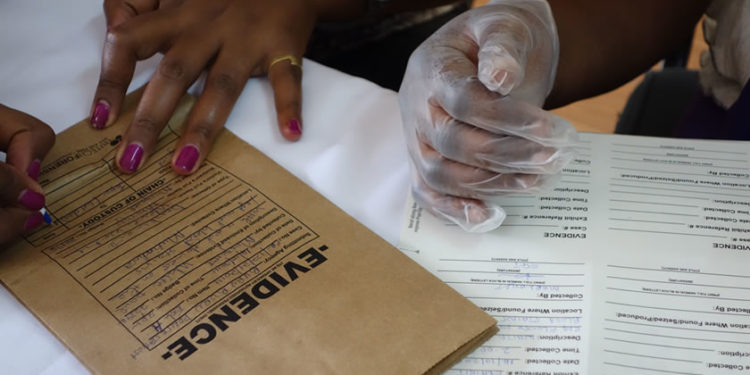

“When participants went back to the field, there was a great improvement in the first few months” because police and doctors were calling the Government Chemist for help. “We are not encountering loose ends everywhere.” With time, she says, the chain of custody is getting tighter and this has enabled survivors to obtain justice from the courts.

Nyakundi Nyatete, a police officer based in Nakuru, was elated after his training: “I now know how to conduct proper forensic investigations in a crime scene including how to conduct interviews with survivors of sexual violence,” he said. The training also build his confidence so much that he can now present evidence in the courtroom.

“We were even given materials to use in the field, including packaging bags for storing exhibits and the chain of custody forms, which we previously lacked,” he added.

Recently, Nyatete handled a defilement case involving a five-year old by speaking to her and her mother to allow for the minor’s soiled clothes to be taken for analysis at the Government Chemist.

The case reached court and the girl achieved justice. “All because I used polite language with the girl and her mother,” he adds.

Constable Kipng’eno Koskei remembers many instances when the police would use plastic paper bags to package evidence for presentation to the Government Chemist for analysis, only for it to be rejected. “I have learnt about the proper packaging of evidence, the kind of knowledge I lacked as a police investigator,” says the Kariobangi Police Station-based officer.

Most police officers are not keen to interview victims of rape. In many instances, officers shout at survivors, thus intimidating and even ridiculing them. It makes it difficult to secure their cooperation. Nyatete knows now that rough handling of survivors re-victimises them to the extent that some might decline to cooperate with the police or health workers and unwittingly lead to the exclusion of material that would have helped to tie up a case.

Milka Cheptinga, an Eldoret-based legal aid officer, says that lack of coordination overburdens a survivor who has to go through all these processes alone, hence ends up feeling victimised and not cooperating properly with those collecting evidence from her.

Post-rape care almost none existent

Many hospitals in Kenya do not have a specialist unit for sexual violence. Survivors are, therefore, attended by any practitioner, trained or not.

Clinical officers face difficulties in filing medical evidence in the post-rape care (PRC) form used to document the injuries sustained by the survivor, history, and any samples collected.

At Nairobi’s Mbagathi Hospital, a nurse revealed that filling the PRC form is a lengthy process most of her colleagues abandon halfway through to attend to other patients. Police officers feel frustrated when certain details are not included in the medical documentation.

“How can we improve accountability and address impunity for these crimes if we are missing adequate evidence to sufficiently push these cases forward?” Naimer asks at the start of her training sessions. “We hope to break the vicious cycle of sexual violence.”

She hopes that the training can dramatically increase local capacity for the collection of court-admissible evidence of sexual violence to support prosecutions.

Corporal Joseph Kibet, who is attached to the Criminal Investigations Department in Wajir County, notes that a vast majority of police investigators do not have the skills and equipment to carry out forensic investigations in rape cases. He previously worked as an investigator in Eldoret, handling sexual violence. “DNA evidence is an integral part of police investigation of a rape because it can build a strong case to show that a sexual offence indeed took place.” He laments that majority of his colleagues are not trained in the collection of DNA samples from the crime scene.

Another significant gap is the lack of measures to ensure confidentiality and protection of the chain of custody for obtained evidence, including lack of specific forms to record transmission of evidence from one sector (chain) to another. Joint training for the police, health staff, laboratory technologists, prosecutors and judicial officers has reduced the misunderstanding that often produces buck-passing in securing justice for sexual violence crimes.

Hope for justice

More than ever, trainees understand the expectations and challenges in each other’s respective sectors and how they can work together.

Leah Gichia, a nurse at Kayole II Hospital, in Nairobi, says the refresher course on how to fill the PRC form was the best for her. Before the training, she had never seen the form — even though she had been treating survivors of sexual violence. “The trainings have made me to get closer to my patients. Initially, I handled them with a lot of ignorance or referred them to other nurses. Previously, [I avoided] anything to do with the police. I even used to discourage my patients a lot telling them to brace for a long journey with the police. But since I started coming for these trainings, I like to tell my patients that they are on the right route.”

Training is also helping the experts in other ways. Dr Justus Nondi is an obstetrician and gynaecologist at the Kenyatta National Hospital. He trains trainers, and reckons that the greatest contribution of the exercise has been demystifying the role of the different stakeholders, more importantly, the police.

By regularly interacting with lawyers and judges in training meetings, he is no longer intimidated by the prospect of attending court, unlike before when he would sweat and stutter when confronted with tough questions in court.

Dr Michael Oduor of Kenyatta National Hospital says: “We are ignorant of what our other colleagues in other sectors are doing yet we are working with them towards bringing justice to these sexual offence victims.”

Charles Mbogo, the chief magistrate at the Malindi Law Courts, first attended training after the 2007-2008 post-election violence in preparation for the 2013 elections. “We were trained on how to deal with sexual and gender-based violence which was quite prevalent during PEV,” he says.

“Since all of us are working together towards achieving the same goal, we need to understand what our fellow stakeholders go through so that we are able to understand each other.” He says this networking reduces the blame games so prevalent between different sectors.

“Today, we are able to give objective evidence in a court of law,” says Rose Wafubwa, a nurse in the emergency department at the Kenyatta National Hospital.

“Forging relationships between various sectors is crucial for helping survivors to bring their cases to court because this ensures a seamless process from when a survivor reports her case to the police up to when judgment will be made in court,” says Doreen Osiemo, a nurse at the Nairobi Women’s Gender Recovery Centre.

Experience has taught Kibet that police investigators need to have the telephone contacts of medical offiers dealing with sexual offences.

If a victim decides to report a case to a police officer first before a medical doctor, they need to know where to look first to seek evidence. Kenyan workers trained by PHR have created Whatsapp messaging group to help them refer cases among themselves, share ideas and discuss challenges they all face in their work.

Survivors, too, are not being left behind. Mutere says she now appreciates the importance survivors of rape preserving evidence by not taking a bath or washing up after the incident. Often, survivors are subjected to many procedures that require her full participation and can sometimes be in the hands of unprofessional officials who do not coordinate with one another. In such circumstances, patience can make the difference between securing justice and giving up altogether.