The death of former Rwandan politician, businessman, and administrator Protais Zigiranyirazo in Niger last week turned the spotlight on one of international justice’s most troubling chapters.

Known simply as Monsieur Zed (“Mr Z”), the brother-in-law of Rwanda’s former president, Juvénal Habyarimana, died not as a convicted war criminal, but as a man who had been unanimously acquitted of all charges, yet remained in limbo due to circumstances beyond the tribunal’s power to resolve.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) had cleared him of all charges and he should have walked free that day. Instead, he spent the next 16 years of his life in various forms of detention, dying under effective house arrest in a compound in Niamey, Niger, still fighting for the freedom the courts had said was rightfully his.

Zigiranyirazo wasn’t just any defendant. As the president’s brother-in-law, he was closely connected to Rwanda’s political elite. After his arrest in Belgium in July 2001, the ICTR first accused him of crimes against humanity and later amended the charge to committing genocide against Tutsis between April and July 1994 in Kigali and Gisenyi. On December 18, 2008, Trial Chamber III convicted Zigiranyirazo of genocide and extermination as crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 20 years in prison.

However, on November 16, 2009, ICTR Appeals Chamber reversed Protais Zigiranyirazo’s convictions and entered a verdict of acquittal. The court cited serious factual and legal errors in the Trial Chamber’s assessment of his alibi and other evidence, found that there had been a miscarriage of justice, and ordered his immediate release.

The decision brought relief to the defendant. The legal effect was unambiguous: in international criminal law, acquittal is final and binding. There are no “degrees” of innocence. Yet the decision provoked outrage in Rwanda, where survivors’ groups and the government rejected it.

“This acquittal decision shocked the Rwandan nation and the Rwandan people and perhaps also Zigiranyirazo himself: he knows he’s not innocent,” Rwanda’s Justice Minister at the time, Tharcisse Karugarama, reacted sharply.

Legally, however, the matter was settled — Zigiranyirazo was innocent. The controversy lay not in the legal judgment, but in the political and social perceptions that illustrared the tension between judicial findings and the lived realities of post-genocide reconciliation.

Stateless and unwanted

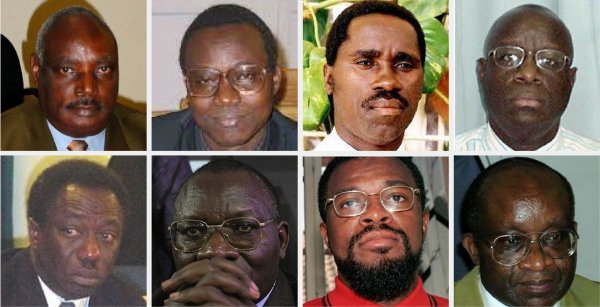

He and seven other ICTR-acquitted or released persons soon discovered that even an acquittal does not automatically resolve questions of resettlement. Certainly, Rwanda was not ready to accept back Zigiranyirazo, André Ntagerura, Tharcisse Muvunyi, Anatole Nsengiyumva, Alphonse Nteziryayo, Francois-Xavier Nzuwonemeye, Innocent Sagahutu, and Prosper Mugiraneza as free citizens, instead viewing their presence as politically toxic. Western nations, despite their vocal support for international justice, were equally reluctant to offer sanctuary. No country wanted them.

The eight men found themselves in legal limbo – with some states treating them as politically dangerous despite their legal innocence, leaving them with nowhere to go. They became what advocates called “the stateless”, human beings caught between political realities and legal principles.

ALSO READ: Elusive Sanna Manjang continues to rob Gambian victims of hope for justice

In December 2021, Niger finally agreed to take them in from the Tanzania-based United Nations International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT), the successor institution to the ICTR and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), but this wasn’t the freedom they’d been promised. Instead, they found themselves restricted to a residence in NIger’s capital, under constant police watch, supposedly living “freely and permanently” but in reality, still without papers and genuine freedom.

A pattern of deaths

Zigiranyirazo’s is the third death among the eight men transferred to Niger – Muvunyi died in June 2023, and Nsengiyumva in May 2024. That’s a mortality rate that would alarm any prison warden, yet these men weren’t supposed to be prisoners at all. They were meant to be free citizens of Niger, rebuilding their lives after years of legal battles. The reality, as described by their lawyer Peter Robinson, paints a grimmer picture.

“Indeed, with the death of Protais Zigiranyirazo, three of the eight men transferred to Niger have now died in the house in Niamey to which they had been confined,” Robinson explained in an email to Journalists for Justice (JFJ).

“Last year Judge Joseph Masanche of the Mechanism issued an order to show cause why the men could not go back to Rwanda. We all filed submissions explaining the dangers they faced there. Judge Masanche has not issued any decision on his order to show cause in over a year,” added Robinson, who has spent over two decades defending clients at international criminal tribunals.

Life in limbo

The reality of these men’s lives reads like something from a Kafka novel.

Describing their daily routines, Robinson said: “The men’s freedom of movement has eased somewhat, and they are able to leave their residence from time to time. The police remain stationed at their residence but will escort them to various places around town for medical appointments, groceries, etc.”

But even these small freedoms come with humiliating restrictions.

“The government of Niger has so far refused to return their residence papers, so they have no way to open bank accounts, obtain goods on credit or any other forms of normal life,” the lawyer noted.

He added that the UN Registrar has been trying to help, providing rent and subsistence since the men cannot support themselves. They remain under an expulsion order that has been “in limbo” for more than three years, unable to establish any semblance of normal life. “The Registrar has been trying to convince the Niger government to provide them with such documents, but so far with no success.”

The system’s failure

Perhaps most damning is Robinson’s assessment of the international justice system’s response: “The Registrar’s efforts to find them another country have all but stopped as there are no prospects for success in this venture so long as Rwanda objects to their resettlement anywhere.”

This reveals the paradox of international criminal justice. Courts can declare someone innocent, but if powerful states object to that innocence, legal findings become meaningless. Rwanda’s continued opposition to these men’s resettlement effectively overrides judicial decisions made by international tribunals.

“It is indeed a major injustice to be detained after you have been acquitted or served your sentence,” Robinson stated. “The Mechanism has been completely powerless to remedy this injustice over the past four years.”

The Association of Defence Counsel practising before the International Courts and Tribunals (ADC-ICT) described Zigiranyirazo’s situation in their press release dated August 12, 2025, as representing “one of the most pressing and unresolved issues facing the international justice system.” They argued that “continued restrictions on liberty after acquittal, or after the completion of a sentence, not only violate fundamental human rights but also undermine the credibility of the very institutions mandated to uphold justice.”

This isn’t hyperbole. When acquittals become meaningless because no country will honour them, the entire premise of international criminal justice is brought into question. What’s the point of fair trials if the verdict only matters when it’s convenient for powerful states?

The irony in Zigiranyirazo’s fate is that he was accused of being one of the architects of the genocide in Rwanda, yet his acquittal was ignored by the very international community that created the courts that tried him. Meanwhile, other genocidaires who were never caught continue to live free around the world, their crimes unpunished and their movement unrestricted.

The eight men in Niger became unwitting pawns in a larger game of international politics, their legal status subordinated to diplomatic convenience. They were acquitted, yet denied the genuine freedom that should have followed their acquittal.

Behind the legal complexities lies a simple human tragedy. Zigiranyirazo spent his final years confined to a compound in Niger, dependent on UN handouts, unable to live a normal life despite being acquitted. His family couldn’t visit easily, he couldn’t work or travel, and he died knowing that, while the court had acquitted him, the international community had failed to honour that decision.

ALSO READ: New status conference to ponder Kabuga’s fate

The remaining five men in Niger face the same fate. They wake each day knowing that their legal innocence means nothing, that they remain prisoners of international politics rather than international law.

Time for accountability

The ADC-ICT called for “urgent and concrete measures to ensure that acquitted persons and those who have completed their sentences can enjoy the full freedom to which they are entitled. “This isn’t radical – it’s basic justice.

Zigiranyirazo’s death should prompt the international community into action. The situation of the Rwandan men stranded in Niger exposes the fundamental hollowness of international criminal justice when political considerations override legal findings. If acquittals can be ignored, trials risk becoming meaningless exercises in legal theatre.

The international community created these tribunals to ensure accountability for the world’s worst crimes. But accountability works both ways. When courts acquit someone, that decision must mean something, or the entire system risks losing its legitimacy.