As the new administration prepares to assume office after the election of the new chancellor, stakeholders of international law and justice will be watching to see how the Federal Republic of Germany will walk the diplomatic tightrope between its historical commitments as a staunch ally of Israel and its obligations under international law in the face of the controversy surrounding the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

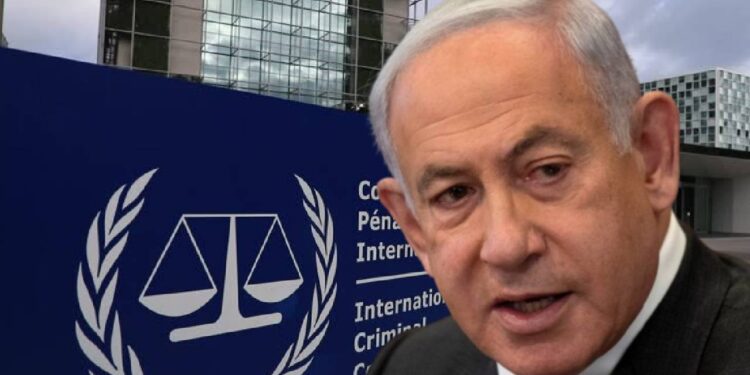

In February 2025, after his party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), won the elections, Friedrich Merz, who was expected to be elected as the next chancellor, said he would invite Netanyahu to visit Germany, promising to find a way for the Israeli Prime Minister to escape arrest under the warrant issued in November 2024. The warrant, for the alleged “war crime of starvation as a method of warfare and the crimes against humanity of murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts” in the ongoing Gaza conflict, covered Netanyahu and his former defence minister, Yoav Gallant, as well as Hamas commander Mohammed Diab Ibrahim al-Masri, better known as Mohammed Deif, who is now deceased. The Gaza Health Ministry has reported that since October 2023, when the conflict started with the Hamas attack on Israel that killed about 1,200 people, some 48,388 Palestinians have died, with 111,803 others sustaining injuries.

“If he [Netanyahu] plans to visit Germany, I have promised myself that we will find a way to ensure that he can visit Germany and leave again without being arrested. I think it’s a really absurd idea that an Israeli prime minister can’t visit the Federal Republic of Germany. He will be able to visit Germany,” Merz was quoted as saying by Deutsche Welle.

Merz’s invitation has been criticised by the ICC, international justice organisations including Amnesty International, and opposition parties in the central European country.

Read Also: No easy road to ICC justice for Kenya’s victims of abduction and extrajudicial killing

In a statement, the ICC affirmed that Germany, having ratified the Rome Statute in December 2000, is obligated to enforce its decisions. “It is not for states to unilaterally determine the soundness of the court’s legal decisions,” the court said.

According to Jan van Aken, the co-leader of Germany’s Left, Germany must enforce the warrant against Netanyahu in the same way it would respond if Russian President Vladimir Putin were to visit. Putin is also wanted by the ICC for the war crime of unlawfully deporting and transferring children from occupied territories in Ukraine to Russia.

“If Vladimir Putin comes to Germany, then this arrest warrant must be implemented. The same applies to Netanyahu,” said van Aken.

“We respect its [the ICC] procedures and the decisions of its organs. This applies without exception,” said Nils Schmid, the foreign policy spokesman of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). The SPD, the party of outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz, has aligned with Merz’s CDU/CSU (Christian Social Union) alliance, which won Germany’s election in February with 28.5 per cent of the vote, to form the new government in Germany.

Champion of international law and justice

Amnesty International stated via X: “Not a good start as future chancellor: on the evening of the Bundestag elections, Friedrich Merz apparently invites Benjamin Netanyahu to Germany, against whom an arrest warrant has been issued by the International Criminal Court. The new German government must respect international law and human rights institutions. For a foreign policy without double standards.”

The arrest warrant is an inconvenience that the new leadership in Germany finds difficult to accommodate as it has placed it the on the proverbial horns of a dilemma: how to maintain the state’s “special relationship” with Israel, which the two states have painstakingly built over more than seven decades, without jeopardising its image as a champion of international law and justice.

In the years following the Second World War, Germany has extended significant military aid and reparations to Israel as part of its commitment to atone for the Holocaust, even in the wake of the accusations against Israel of war crimes and genocide in Gaza, as well as allegations by human rights organisations of apartheid, which is a crime against humanity. South Africa, having experienced apartheid first-hand, has taken a hard stance against Israel’s actions in Gaza and filed a case against it at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Through their shared diplomatic cooperation, the top leaders of Germany and Israel have paid numerous state visits to each other and even addressed the legislative assemblies of their respective partners.

The ICC arrest warrant against Netanyahu now appears to threaten their close ties as it tries to make Germany turn against its long-time ally.

International arrest warrant

The invitation has also raised concerns about Germany’s commitment to the ICC. Germany is one of the 137 signatories to the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the ICC, which requires members to arrest suspects on their territory. Germany has built a reputation as a strong supporter of the court and has in the past insisted that international arrest warrants must be honoured.

The warrant also threatens to undermine the image of Germany as a strong champion of international law and justice. The country has built a reputation as an active participant in the international justice system and a strong supporter of the ICC.

In the words of Ambassador Pascal Hector to the 14th Session of the Assembly of States Parties in November 2015, “My country’s unwavering support for the International Criminal Court is founded on German history in the 20th century. Re-establishing the rule of law was key to overcoming our troubled past.”

The Federal Republic of Germany is one of the countries that has adopted the principle of universal jurisdiction, developing a legal framework for prosecuting crimes committed abroad, even if the perpetrator or victim is not a German national. It has prosecuted several international crimes through this principle. Officials have explained that this is one way of preventing the country from becoming a “safe haven” for international perpetrators while at the same time promoting justice for victims who have found refuge in Germany.

It also adopted the Code of Crimes Against International Law (CCAIL), which allows Germany to prosecute international crimes at the domestic level, ensuring that individuals who commit such crimes are held accountable.

Germany has integrated the decisions of the International Court of Justice into its legal system, recognising the ICJ’s role in international law.

If Germany disregards the ICC and welcomes Netanyahu on its territory while the arrest warrant is still in force, it will be joining a long list of Assembly of States Parties members who have flouted their obligations to the ICC by failing to arrest wanted suspects and thus helped to undermine the court’s authority.

In 2025, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni sparked a row after her government let Libyan national Osama Najim (Osama Al-Masri) travel back to Libya despite an outstanding ICC arrest warrant against him. Al-Masri is accused of rape, torture, and crimes against humanity committed in the Mitiga prison, east of the Libyan capital, Tripoli, starting as early as 2015.

The warlord, who was alleged to be in charge of prison facilities in Tripoli, was arrested in Turin, where he had gone to watch a Juventus-Milan football match. He was freed due to a legal technicality and flown back to Libya on an Italian government flight, drawing an outcry from opposition leaders, rights groups, and victims.

“The injustice we suffered, and how Italy became complicit in our eyes, is clear. They took justice away from us. Our torturer was in Italy, he was arrested, and then he was smuggled back to Libya,” David Yambio, a South Sudanese who suffered abuse in Mitiga prison, told the BBC.

Italian Justice Minister Carlo Nordio defended the decision to send al-Masri home, claiming the ICC had issued a contradictory and flawed arrest warrant. The ICC denied the claims and opened an inquiry into Italy, demanding answers for the state’s non-compliance.

In September 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin received a red-carpet welcome in Mongolia despite calls for his arrest for alleged war crimes related to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. This was his first visit to an ICC member nation since the warrant was issued in March 2023.

Former Sudanese president Omar al Bashir has been at the centre of conflicts involving the ICC and Kenya (2010), South Africa (2015), and Jordan (2017). He is wanted by the ICC for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in connection with the conflict in Darfur, which caused about 300,000 civilian deaths and displaced 2.7 million people between 2003 and 2008. He has two outstanding arrest warrants issued against him in 2009 and 2010.

Centre of conflicts

Kenya ignored the ICC in 2010 and hosted Bashir during the promulgation of its new constitution, claiming he had immunity as a head of state. The Kenyan High Court later ruled that Bashir should be arrested if he ever returned. The ICC, on its part, ruled that Kenya was obligated to cooperate and arrest Bashir and reported the country to the ASP and UNSC, but no action was taken.

South Africa was required to arrest Bashir during an AU conference in Johannesburg in 2015 but argued that he had immunity based on customary international law and the Host Agreement with the African Union. The visit led to litigation in the domestic courts and initiated the process of South Africa withdrawing from the ICC. In 2017, Pre-Trial Chamber II stated that South Africa’s inaction was contrary to the Rome Statute but did not refer the matter to the United Nations Security Council.

Jordan refused to arrest Bashir during the Arab League Summit in Amman in March 2017, citing immunity under customary international law and the 1953 Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the Arab League. The ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber rejected the argument in December 2017, ruling that Bashir did not have immunity under the 1953 Convention and that Jordan was obligated to arrest and transfer him. The Chamber referred the matter to the ASP and the UNSC.

President Donald Trump hosted Netanyahu at the White House in February and in April 2025, amid protests over the US government’s double standards in international law. The US is not a state party to the Rome Statute.

In November 2024, then-outgoing President Joe Biden termed the arrest warrant against Netanyahu as “outrageous, unlawful, and dangerous”, saying there is “no equivalence between Israel and Hamas”.

“We remain deeply concerned by the prosecutor’s rush to seek arrest warrants and the troubling process errors that led to this decision. The United States has been clear that the ICC does not have jurisdiction over this matter. In coordination with partners, including Israel, we are discussing next steps,” a statement from the White House’s National Security Council read in part.

The “next steps” would come in February when Trump issued an executive order imposing sanctions on the ICC, asserting that the court had no jurisdiction over the US or Israel.

“The ICC’s recent actions against Israel and the United States set a dangerous precedent, directly endangering current and former United States personnel, including active service members of the armed forces, by exposing them to harassment, abuse, and possible arrest,” the order said.

The ICC relies on the cooperation of ASP members for the enforcement of all its decisions, including the execution of arrest warrants.

In April 2025, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban welcomed Netanyahu as he arrived for a state visit. Soon after that, it was announced that Hungary would be withdrawing from the International Criminal Court. Orban had invited Netanyahu as soon as the warrant was issued in November 2024.

Currently, more than a dozen individuals with ICC arrest warrants remain at large, including Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) warlord Joseph Kony and Bashir. The individuals face a total of 206 charges, including 87 counts of crimes against humanity, 116 counts of war crimes, and three counts of genocide.

The court has withdrawn warrants for at least four individuals, including Hamas leader Mohammed Deif, who died before they could be apprehended.