It has been a decade since the International Criminal Court (ICC) opened its investigation into alleged mass atrocities committed in Darfur.

Those ten years have been, to say the least, a rocky ride for international justice. No official from the ICC has ever stepped foot on the Sudanese region. Despite a series of arrest warrants issued against alleged perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, there is no real prospect that anyone will be convicted. The international community has, by and large, turned a blind eye, leaving ICC prosecutors with little choice but to shelve their investigation. Today, the person receiving the most attention is the same person allegedly most responsible for human suffering in Darfur: Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir.

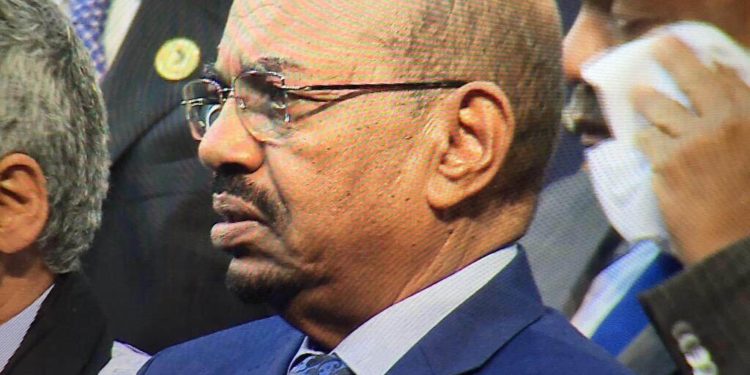

It seems that Bashir is constantly in the news. Despite two arrest warrants issued against him by the ICC, Sudan’s president has managed to travel to a number of countries in recent weeks and months, mostly notably to three of the so-called BRICs states: South Africa, China and India. Bashir’s state visits are no doubt a source of great frustration for proponents of the ICC, many of whom had previously insisted that the Court had severely restricted Bashir’s ability to travel. But Bashir’s gallivanting also points to the unfortunate combination of the ICC’s inability and the international community’s unwillingness to achieve any kind of justice for crimes in Darfur. And make no mistake: the primary loser of this impasse is not the Court or the advocates of international law. It is the victims of mass atrocities in Darfur.

The ICC prides itself as an institution that promotes the role of victims in its work and mandate. Granting victims rights as well as allowing them to participate and have legal representation at the ICC is what the Court calls a “great innovation”. There is no doubt that the ICC’s focus on victims is a crucial and significant improvement from the institution’s predecessors, the International Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, where victims were, in principle and practice, only permitted to participate in proceedings as witnesses.

But what does the Court’s interest in victims truly mean? In their article on the subject, Sarah Nouwen and Sara Kendall have argued that the role and representation of victims at the ICC is severely limited and remains more abstract than real:

[I]n the practices of the ICC—which in this context involves not merely the Court, but also the epistemic community surrounding it—victims are both overdetermined and less represented than the claims suggest. They are overdetermined in that all victims are amalgamated into an abstract entity, ‘The Victims’, which serves as a rhetorical justification and rationalisation of the project of international criminal law. Meanwhile, as a result of juridification, very few individuals are actually personally represented in legal proceedings. This gap between the discourse surrounding victim representation and what transpires in the Court’s work, namely between the presentation of ‘The Victims’ as the raison d’être of international criminal law and the very limited role of victims in international criminal proceedings, coincides with a gap between the victim as an abstraction and as an actual victim of mass atrocity.

These views are shared by insiders. Based on a lecture given by former ICC Judge Adrian Fulford, a Chatham House report observed that “the way in which victims come to participate has been described as both arbitrary and highly selective”.

Court officials certainly take these criticisms and shortcomings seriously, as evidenced by former Fulford’s comments on the matter. Moreover, as Chris Tenove has written, while “we still lack in-depth assessments of the impact of victim participation in different cases, [t]here is clearly a desire at the ICC to continue to improve victim participation”.

As the Court matures, it will get better at managing expectations and will more effectively integrate victims into proceedings. But sometimes victims will give up on ICC justice altogether. A year after ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s decision to hibernate the Court’s investigations in Darfur, a group of victims, representing almost half of those involved in the Bashir case, has decided to do just that. In a motion filed by their legal representative, eight victims from Darfur notified the Court of their intention to withdraw from the case against Bashir:

In light of the inability to advance the prosecution of the al-Bashir case since 2009 and in light of the Prosecutor’s decision to suspend “active ”investigations into the Darfur situation in late 2014, the Legal Representative has reached a confidential settlement agreement in the interests of the Participants mentioned above.

In the circumstances, Victims a/0443/09, a/04 44/09, a/0445/09, a/0446/09, a/0447/09, a/0448/09, a/0449/09 & a/0450/09 will seek no further role in the al-Bashir case nor, for that matter, in the Darfur situation. Without waiving any right to protection and to confidentiality of their identity, the Participants will not object to the removal of their participatory rights in the case against Omar Hassan Ahmed al-Bashir.

The Prosecutor’s honest and tough rebukes of the United Nations Security Council regarding the international community’s dithering on Bashir and Darfur were widely, and rightly, praised. But the decision to shut down investigations also came at a clear cost to the victims and survivors whose expectations were elevated when, in 2005, the Council referred Darfur to the ICC. Today, both the Council and the Court are responsible for raising those expectations. But whatever aspirations victims had that the ICC would be able to deliver on the promise of accountability have now been dashed. It is a sad day when the very victims in whose name ICC justice is pursued give up hope that accountability can or will ever be achieved.

A version of this article originally appeared for Courtside Justice at Justice Hub.