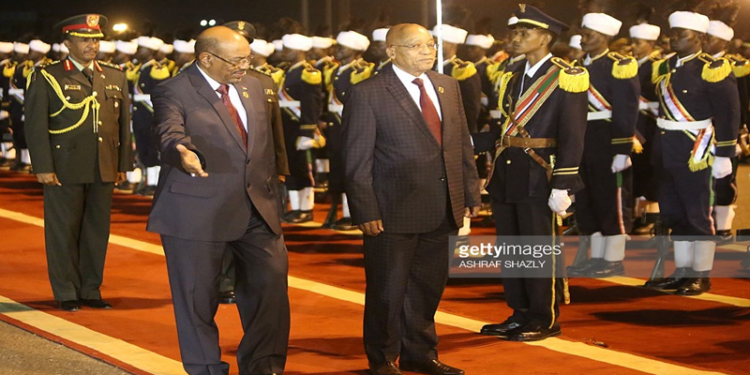

South African President Jacob Zuma met his Sudanese counterpart Omar al-Bashir last year.

By Ottilia Anna Maunganidze

On Tuesday, March 15, the South African Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) dismissed the government’s leave to appeal the finding of the High Court that it should have arrested Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir when he came to the country in June 2015. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued two arrest warrants for al-Bashir on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in the western Sudan region of Darfur. It is on the basis of these warrants and South African law that South African authorities could have arrested al-Bashir, but didn’t.

In the decision, the SCA found that in not arresting al-Bashir, the South African authorities’ actions were inconsistent with existing legislation and ultimately unlawful. The SCA was also very critical of the government’s conduct during the High Court proceedings that they were seeking to appeal. The lawyer for the state had, several times during the proceedings, reassured the court that al-Bashir was still in South Africa. This despite widely circulated images on social media showing al-Bashir’s motorcade arrive at Waterkloof Airbase, as well as the Sudanese presidential jet leaving the base. Calling the government’s conduct “disgraceful”, the court raised concerns that the government and/or its lawyers misled the High Court. Al-Bashir indeed left the country just when proceedings at the High Court had started.

For the South African government, the issue – at least today – is fairly simple: international criminal justice is important, but sitting heads of state must enjoy immunity from prosecution (even for international crimes) and thus cannot be arrested. This view was enunciated by President Jacob Zuma in October 2013 following an extraordinary African Union (AU) Summit to discuss Africa’s relationship with the ICC. It is certainly not a new view.

The South African government’s position in 2009 was slightly more nuanced. The then Director-General of the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO), Dr Ayanda Ntsaluba, stated that while al-Bashir had been invited to President Zuma’s inauguration, he had been warned against attending. The department, aware of an arrest warrant issued by a magistrate in Gauteng, had advised al-Bashir not to travel because he risked arrest.

To be clear, the department was not at the time saying that al-Bashir did not enjoy immunity. That issue was somewhat skirted. Instead, it was saying it could not control what the courts and the criminal justice officials would do. Puzzling, as this may seem, the departure thus was not in a view that al-Bashir should be arrested, but rather that in 2009 the department of international relations could not guarantee that he would not be arrested.

This thus raises questions as to whether the South African government’s position on international criminal justice has changed. The answer lies in how far back into the country one goes. At least from 2009 (and even in the years immediately prior when former president Thabo Mbeki voiced his opinions on immunity), the view has largely remain unchanged, though it has hardened.

Going further back to 2002, South Africa’s position has definitely changed. It would be interesting to hear the views of the crafters of the Implementation of the Rome Statute Act, who in 2002 saw it fit to frame the law in a way that ensured all men (presidents included) are equal. It is that law that they drafted 14 years ago that has empowered judges at various levels to decide against government action.

The SCA rebuffed the government’s arguments regarding immunity of heads of state. While acknowledging that in customary international law this issue is not yet resolved, the judges instead made (and, arguably, rightly so) reference to South African law.

The majority of the judges were of the view that the Implementation of the Rome Statute of the ICC Act effectively does away with immunity from prosecution for international crimes and that the Diplomatic Immunities and Privileges Act should be read with this in mind. Using a purposive constitutional interpretation of South African law, the judges found that the Implementation Act should be seen as a tool to promote and protect rights contained in the South African Constitution. The Act, the SCA found, does this by criminalising gross human rights violations. This was a significant pronouncement.

Heralded by civil society as a landmark judgment, this decision – coming from the country’s highest court on non-constitutional matters – dealt a big blow to the South African government’s stance.

Of course, indications are that the government will likely appeal to the Constitutional Court. This would buy it more time, since the ICC is still waiting for the South African government to submit its reasons for not complying with the ICC’s request to arrest al-Bashir. South Africa was granted a postponement until domestic legal processes were completed. With the SCA decision, the deadline is drawing even closer.

In the meantime, questions are still lingering about who should be held responsible for what the SCA calls ‘unlawful’ and ‘risible’ conduct on the part of the government.

If the Constitutional Court, should the government appeal to it, endorses the decisions of the SCA and the High Court, then investigations into who was responsible would have to follow. The rule of law demands it. Whether they will, remains to be seen.

Ms Maunganidze is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa